Whoo boy. This is what I get for taking requests on topics. Unreliable/untrustworthy/unstable Narrators (from here on out I’ll just call them unstable, but I refer to both). I’ll be honest, I actually held off on this one for a while, waiting until I could crystallize some thoughts on it that felt solid enough to write up. Unstable narrators are a tricky topic, as well as a tricky tool in the writer’s toolbox, and I wanted to make sure that if I tackled it, I had some advice to give.

Well, thanks to some good thinking, as well a recent hands-on experience with using one (not my first, I assure you), I think now is the time.

Unstable narrators. Here we go.

So, simplest place to start: What is an unstable narrator? They’re a PoV character or a narrator (as sometimes a character is not necessarily the narrator) who’s view of things is not entirely correct. We also sometimes call this an untrustworthy narrator.

Simpler? All right. This is a character whose perspective of—or a narrator whose telling of —events cannot be trusted. They are either flavored, faulty, biased, incorrect, or in some other manner not honest with the reader.

To put it another way, a story with an unstable narrator is one where the reader cannot fully trust the information that is presented to them, because it’s not perfectly honest. Sort of like asking two six-year-olds who started a fight: Both will give a slightly different interpretation of events. In this case, whatever narrator the story follows, be it a PoV character or the “voice” of the story, is lying to the reader.

Perhaps that’s a harsh word for it, but in essence, it’s the closest to what we’re speaking about here. By the nature of literature, we tend to approach the stories we read at face value: The hero says that she slew seven warriors in lone combat, and we trust her, because the book is supposed to deliver an honest account that we can believe, even if it’s discussing something that is pure fantasy.

An unstable narrator, on the other hand, lies. They don’t tell the whole truth. An unstable narrator might claim that she’s slain seven warriors in single combat, and the book itself may tell you that … but when you read between the lines and look more closely, you find that instead, she only slew four, and she had help. Help she either doesn’t acknowledge to make herself sound more grand, or maybe refuses to acknowledge as a personal weakness.

Now, if this sounds somewhat familiar to you, well, it should. Because with an unstable narrator, we are touching on a topic I’ve discussed many times before, that of the Character Perspective. There, if you’ve read it, I talked about how everything you write from a limited perspective is going to be flavored by the character whose perspective it is.

The difference, lest you start wondering, is that while one is still an pretty truthful account, the unstable narrator, which we’re talking about today, isn’t. Writing in a perspective is like looking through glass: It alters the way we see the outcome. But writing an unstable perspective is like replacing that glass with a funhouse mirror. Things aren’t just flavored, they’re flat out different.

So, we know what an unstable narrator is. Now come real questions: When and why would we want to use one? And how would we do it?

We’ll tackle these in order, since knowing how to use one is a little pointless if we don’t need one or don’t know where to put one.

Why would you use an unstable narrator? What’s there to gain? What would make you want to use an unstable narrator over a more honest one or a regular perspective?

In this case, I’m afraid I must admit I don’t have all the answers to that question. There are probably more uses for an unstable narrator than I’ve thought of here. So while I can give you an answer, take it with a grain of salt, and if you find a spot where one day you realize that there’s a place for an unstable narrator, remember this moment and think “Ah-hah! I found one!”

Anyway, an unstable narrator is best used when you want to either hide something from the reader (and perhaps even the character), lead them astray as to what’s really going on, or engage them on a more involved level. Let’s go a bit more in-depth though, and start with hiding something from the reader or the character.

What I’m referring to here isn’t necessarily a mystery (though it can be), but a scenario in which because of the lens the unstable narrator is giving the reader, certain information is concealed from the reader. For example, in the beginning of the Dusk Guard side story Carry On (spoiler alert!), the reader thinks the main character starts out showing her parents her new airship. But as the scene goes on things start to appear out of place, disjointed. Time seems to skip a little bit, and then a character starts talking who up until that point hadn’t been mentioned in the scene at all, but the character treats them as if they’ve been there all along. Then things really get weird.

The catch? Turns out it’s a dream. Well, nightmare, actually, part of a near-PTSD lapse the character is having after the events of the first story she was in. But the narrative never tells the reader that. At no point does the narrator acknowledge the reality of what’s going on, only what she’s experiencing. Thus, the real root of what’s going on—the character struggling with shock and stress—is kept from the reader for a time.

This can be used in other ways too. Characters can deliberately omit information that they themselves don’t want to admit or acknowledge, thus also keeping that information from the reader (until they spot the holes).

Which does tie very closely into leading the reader astray, though that one is more up to the writer (as you can choose to hide information but be clear that you’re doing it, or play things carefully to lead them astray—and we’ll talk more about that in a bit). Hiding information from the reader can be a way to lead them to think that the direction, purpose, or goal of the story is actually something completely different than it is. It’s a bit like a misdirect, except in this case, the narrator themselves is deliberately, one way or another, misleading the reader, as opposed to the story just making something unobtrusive.

Why is this a tool in the writer’s toolbox? Well, for starters you can use it to really mess with your readers (take this for good or ill as you see fit). For example, what if one wrote a short story that opened with a man on the run from an oppressive government prison he’d just escaped? As the man tries to escape, his pursuers go for blood, and you learn just how horrid they are through little lines and observations, until you’re rooting for him as he fights back and kills several of them.

Only to learn in the end that his pursuers are actually a lot better than they were written to be, it’s the unstable narrator that’s a bit warped, and he was in prison because he was a serial killer.

Whoops. Most readers? They’d be rooting for him. The bad guy. That’s the power of a mislead. Such a story could be used to make a reader re-examine their own choices in life with regards to how they see, perceive, or treat others. Or it could draw a spooky parallel to how thin the lines between good and evil can sometimes be.

Point is, it’s a tool. A tool you can use.

Alright, the other use: To engage your reader.

See, what if you’re reading a story and you realize that the narrator might be unstable. That certain things aren’t adding up? That what you’re being told and what actually happened may in fact be two different things?

Well, if you’re like most, you’re going to start paying closer attention to what’s going on. You’re going to start looking at the details more closely, examining the ins and outs of every situation so that you don’t miss something, because like most people you want to know what’s really going on.

Just like that, the story has made you more involved. It’s asked more of you to pry its secrets out, to figure out what’s really going on, and in that you’re engaged. Old and new passages alike start to take on new meanings as the reader looks over them again—first with the view presented from who or what they suspect of being an unstable narrator, and then with their own lens, one that they’re trying to adjust to counter the narrator’s.

Is this bad? Of course not. It’s not for every story, certainly, but the same is true of all tools in the writer’s toolbox. If you look at your narrative and you think it will work well, you try it. If it doesn’t, don’t use it.

All right, now that we’ve talked about some places where you would make use of it, now let’s talk about the how.

Bear with me, as this is going to be a little confusing if you don’t picture it right. Before on this blog we’ve spoken of a sliding scale between two points, such as show versus tell, character versus plot, and other back-and-forth, give-and-take writing techniques, the idea being that as you move towards one side of the scale, you move away from the other.

Well, I see unstable narrators as a bit like that. Except instead of one sliding scale to keep track of, there are instead two.

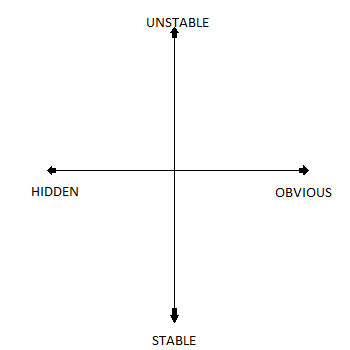

Whaaaaa? Right, right, try to picture this. Envision a sliding scale, a line if you will, moving left to right. On one side, write “hidden” and on the other side “Obvious.” Got that?

Okay, now perpendicular to that line, make another that crosses right in the middle, going top to bottom. On the top write “Unstable” and on the bottom write “stable.”

If you’ve actually written this out, you’ve just created a quadrant graph. Algebra’s revenge at last! Thought you could avoid it with an English degree, didn’t you?

*cough*

Anyway, what you have here is what I like to think of as the “Dual scale of an Unstable Narrator,” which you can see to the right there.

Now, this dual scale is the sliding back and forth that I like to use when I’m coming up with an unstable narrator or PoV character. So let’s go over each of the terms.

Now, this dual scale is the sliding back and forth that I like to use when I’m coming up with an unstable narrator or PoV character. So let’s go over each of the terms.

First of all, stable versus unstable. This is the scale that determines how much of the world the character is going to accurately represent. The more stable they are, the more “honest” the narration is with the reader, while the more unstable they are, the less “honest” they are. I use quotes because remember, as far as the narrator is concerned, they’re giving you the version of events you need to hear, true or not (and whether or not they believe it). So a more unstable narration will omit more, lie about more, or be less honest than a stable narration. Since this is going to flavor everything you write, you’d best make this decision early.

Now to the other two, hidden and obvious. This is about how clear you’re going to make it to the reader that your narrator is unstable. Confused? Well, consider this. Do you want your reader to know that the narrator is unstable and untrustworthy from the get go? Then you want to make it obvious from very early on that something is up. Want to conceal it? Well then you’d best know early so you can avoid spilling the beans.

Now, in picking these two points, you’re going to have a guideline for your story. For example, when I wrote Ripper, in Unusual Events: A “Short” Story Collection, I made the main character only somewhat stable (she’s definitely off) while edging more towards obvious with the fact that she was off, which before long, made it clear to the reader that everything the character said was suspect.

On the other hand, you could have a very obviously stable character (which is almost a regular PoV), or an unstable but hidden character (where the reader doesn’t realize they’ve been lied to until the very end).

Basically, in using this sliding scale, I can remind myself exactly how far I want to push each facet of the story in any direction and tailor my writing accordingly on how much I want to reveal or not about my narration’s trustworthiness. From there, everything is tailored.

Right, one last little thing to tackle. What if you’re writing a fantasy or a sci-fi universe, ie a universe that’s not perfectly similar with our own, how do you convey to the reader what they should trust and what they shouldn’t if you’re using an unstable narrator? For example, if the sky isn’t blue for some reason, and our reader knows they shouldn’t trust their PoV character, what do we do to convey that there is some information we can trust?

Easy, you either introduce it via or have reinforced by another character. If another character whose perspective or view the reader trusts or has no reason to doubt also concurs with or observes something about your world (like say, fairies existing), then the reader can reasonably assume that such a fact is true. Unless of course you’ve got a bunch of unreliable narrators, but that’s a different case.

Basically, if you reinforce certain things, the reader will understand that even though some information is suspect, there are things they can trust.

All right, that does it for this post! Remember what an unstable, unreliable, or untrustworthy narrator is for. Ask yourself what they’ll contribute to your story, how you want to use them in order to accentuate whatever you write for your reader.

Then think of the scale and set out to create your narration based on those two points. Knowing what you’ll use it for will help you figure out where to place your narration as you write it and how.

See you next week!